I had written before that I wouldn’t touch on No Longer Human again until I had read the novel and also seen the arc in Aoi Bungaku, but after getting about halfway through the novel, I felt compelled to note the drastic differences between the two. Spoilers for the first episode and first half of the novel.

The anime begins in the middle of the story and, most notably, the spotlight is on Tsuneko, the hostess that would later attempt to commit double suicide with our protagonist, Yozo. The novel, on the other hand, is quasi-autobiographical from the start, excepting the short prologue. The anime seemingly wants to make a sympathetic character out of Tsuneko. She arrives late at the cafe because she was busy looking for her husband. The owners cast furtive glances as she hurries up to the dressing room. This is a big shift in character from the novel where Tsuneko’s husband isn’t missing at all but in jail. In fact, she has given up on him, resolving to never visit him in prison again. The anime makes the curious decision to render Tsuneko as a somewhat faithful woman; yes, she indulges in a one night stand later on with Yozo, but there’s a clear motive behind this action consistent with her portrayal:

She adds a second later, “I’m happy,” because this implies that unlike her husband, he returns for her. This change also bothers me because it doesn’t fit Yozo’s character either. You don’t get the impression that novel Yozo would have returned for her, but we’ll get to Yozo later. To continue, this whole scene isn’t in the novel at all. Not once is anyone chasing after Yozo and not once does Tsuneko have to aid him in anyway. It’s as if Madhouse felt there wasn’t enough action in the source material so they decided to add it. I personally don’t think it adds anything to the understanding of either character–in fact, it completely fabricates a part of Tsuneko’s personality (the loyal woman enduring for her man) that is nowhere to be found in the novel. Personally, the part where Tsuneko hides Yozo under her dress was ridiculous when I first saw it (not to mention that it seems rather well-lit around her crotch), and its absence from the novel just makes it even sillier.

On a similar note, Madhouse introduces an element of mystery into the story that just doesn’t belong. In the anime, it appears as if Yozo pushed Tsuneko off the cliff. Maybe we’re seeing things from his flawed perspective, i.e. we’ll find out later that he didn’t kill her at all but felt guilty about the whole affair. Nevertheless, it’s a stark contrast from the novel where it’s clear that they both jumped in at the same time and he just had the unfortunate luck of surviving. Why did Madhouse do this? Maybe they felt the original story, a psychological profile of a young sociopath, wouldn’t be interesting enough to the audience. I just think this is a little patronizing; I think the original novel is utterly fascinating by itself so all these attempts to add tension to the anime merely serves to obscure the point of the novel: a man painfully trying to explain how emotionally distant he is from the rest of the human race.

My biggest gripe of all: Yozo seems a little too much like an angsty, immature child in the anime.

After uttering this line, Yozo breaks down into laughter and runs off. They portray him as an artistic soul trapped in a rigid lifestyle who then acts out by swindling people. This reduction of his character betrays the complexity in the novel:

Unable to suppress such reactions of annoyance, I escaped. I escaped but it gave no pleasure: I decided to kill myself. — pg. 73

In both representations of Yozo, he expresses his wish to be an artist, but the anime (currently) leaves out an important fact: in the novel, he does nothing but self-portraits. It’s not so much that Yozo is egotistical, but rather, he is trying to understand his true self and art provides that outlet.

The book and dragon mask scene demonstrates the difficulty in translating subtlety from novel to anime. In the anime, the viewers are led to believe that the young Yozo wanted books, but chose the dragon mask because he didn’t want to disappoint his father. This is somewhat accurate of the novel, but the inaccuracies, the missing details, are crucial. In the novel, he cares for neither books nor the dragon mask. Like the anime, he didn’t want to disappoint his father either but there’s a difference: young Yozo feared potential repercussions more than his dad’s disappointment. The anime lacks Yozo’s utter indifference with the human world even at such a young age. When asked what he would really want, Yozo had no real answer; he wanted nothing and could only smile dumbly, a mock representation of how he thought a child should act.

Reading the novel, you get the feeling that you’re reading about a Japanese Patrick Bateman. He’s smart, he’s charismatic and he’s a lady killer. The only difference is that he’s just not a murderer. He cares very little about people, but he does state explicitly that he would never kill anyone:

During the course of my life I have wished innumerable times that I might meet with a violent death, but I have never once desired to kill anybody. — pg. 45

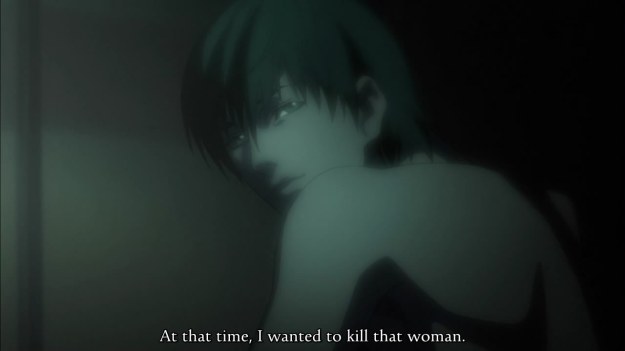

In the anime, on the other hand…

No, he never wanted to murder Tsuneko in the novel; hell, she’s the only person he ever felt like loving.

Yozo in the novel is a fake; ever since he was born, he’s felt different from everyone else somehow. He just doesn’t understand human beings whatsoever and, at one point, he even comments that he doesn’t comprehend what hunger is. That’s not to say that Yozo is a rich kid (he is) and thus has never been hungry; he literally doesn’t understand what hunger is and only eats because it’s something humans do three times a day. Humanity utterly eludes him and every attempt he makes to understand the world around him ends only in disappointment. This point is better elaborated by a review I found of the novel:

In one of my favorite passages, the young Yozo marvels at a bridge built over a railway station, thinking it to have been the product of someone’s urge to beautify their world. He loses interest in it when he realizes it in fact has a wholly boring function: to allow people to cross from one platform to the next. This revelation of fundamental human dullness, as he puts it, is intolerable to him, and he spends the whole of his life trying not to be a creature of such dullness. Unfortunately the only way he is able to do that is by becoming “disqualified as a human being” (the most literal translation of the book’s original title). Each step Yozo takes away from the insufferability of what being “human” means leads him to even greater torment, but never in a way that seems contrived. He’s not running towards anything — just away, always away. — Genji Press (source)

This portrayal is utterly lacking in the anime. Maybe it’s hard to portray a sociopath, but I doubt it. It sounds cynical, but I just get the feeling Madhouse didn’t want to paint Yozo too negatively as major aspects of his youth are left out: his constant clowning, his generalizations and exploitation of women, his utter disgust with the communist movement. There are three episodes left in the arc so Madhouse may eventually touch upon these missing elements of Yozo’s character, but the first episode wasn’t encouraging.

I’ll grant that it’s hard to adapt certain novels, especially something like No Longer Human. The scene above illustrates (no pun intended) this fact quite clearly. What do we take out of it? A dumb smile from a child who doesn’t realize that he’s being raped? The problem is that he does understand what’s going on in the novel; in fact, he calls it the cruelest, vilest thing anyone could do to a child, but he wore a smile out of “weakness.” One might prefer the subtlety of the anime over the blunt directness of the novel, but the latter served a purpose: he told nobody of the rape because of the distance between him and other humans–he feared being argued into silence.

Not everything was a disappointment, however. Madhouse stays true to their roots in delivering powerful scenes in the build-up to the double suicide. The scenes are wordless, but they nevertheless manage to say all that needs to be said.

In comparison, the double suicide in the novel comes and goes with little fanfare. I liked the moments pictured above so kudos to Madhouse in this regard.

I have spent most of the entry voicing my displeasure with the anime adaptation, but don’t get me wrong. As an interpretation of the novel, it takes unnecessary liberties with the source, not to mention completely changing the tone of the suicide into a mystery for no reason. The anime is also an incomplete picture and, as a result, if the anime interests you at all, I highly recommend reading the novel. I will, however, continue to follow each episode of Aoi Bungaku. By itself, the anime is pretty entertaining and gripping. It just has big shoes to fill.

Finally, you allow comments in an entry. I’m glad it’s this one.

I think your criticisms are valid, especially re: anime Tsuneko. But as for the portrayal of Yozo himself, I suggest that you wait until the end of the novel. Get to the very last line, and then consider that the narrative is composed almost entirely of things Yozo wrote about himself. If you have the edition I read in college (which was rather old), the translator mentions something to this effect as well.

I’ve finished the novel. If you’re implying that Yozo was far too negative on himself… that the real Yozo is really an “angel” as claimed by the last line, I’ll have to disagree. Personally, I think the last line is supposed to be ironic. Yozo has been honest about himself from start to finish; he’s a wretched human being–well, not a human being at all. Nevertheless, people around him still think he’s an “angel,” but that’s the point of the novel: the distance between people, the lack of understanding.

I recall a rant near the end by Yozo about society–how society is nothing more than individuals struggling against each other. I think this interpretation of the ending is more consistent with the nihilistic themes of the novel. It just doesn’t make sense any other way. A “good boy” wouldn’t drink his life away. An “angel” wouldn’t have gone from women to women nor walk away to sulk while his wife is being raped. If the epilogue is important (and I’m not denying that it is), then the prologue is equally important and an inhuman reading of Yozo is consistent with the prologue.

If you’re implying something else altogether, then please explain.

Those are good points, but what I meant was more like: The novel has been set up so that we can’t REALLY know who Yozo was. He certainly wasn’t the “angel” people thought he was, but was he really the sociopath he wrote himself to be? After all, it’s clear enough that he could feel anguish. I think it goes back to the point of the novel, as you put it, the distance between people. We, the readers, are no better at bridging that gap.

I don’t like how heavily the father figures in the anime adaptation. It makes it seem like some kind of repressive Freudian thing. But the mystery of Yozo’s motives (she asked him to push her, but he thought he wanted to kill her, but he looked so horrified, but he smiled in the last scene, but but but…) is an addition that I think spices things up in a way that enhances the themes of the original. And, as you say, it’s still quite early.

I finally read the translator’s notes at the beginning and he does argue something along what you are saying. Although I get your point, and it’s not one I can disprove, I still don’t find it convincing. Even supposing that Yozo never really understood himself, he should still be a more reliable judgment of his own character than the others around him by the mere fact that he’s the one “behind the wheels.” Yes, we are not great at bridging the gap as you say, but why should he fail to comprehend his own actions. I never got the impression he was blaming himself or playing the martyr; it just felt like a straight confession. While some details might not be reliable, I just find little to suggest why he would be so excessively negative of himself. Lastly, I don’t understand what makes the madam of the Kyobashi bar the only objective witness, but this is not your words, but the translator’s.

(Not that it means anything, but Dazai wrote this after leaving his wife and child for another woman. Pretty bastard thing to do and then imply later that he’s an “angel,” but I’m only being facetious in mentioning this, not that I think this should sway our discussion.)

But let’s grant that Yozo isn’t as bad as he claims. Two issues come up.

First, I still don’t think the mystery elements fit either way. We may not understand Yozo. He may not understand himself either. But one thing is clear: he has never directly hurt anyone. He has never felt like harming or killing anyone. As a result, the mystery seems inconsistent with the novel. Nowhere in his own notebooks does he suggest any such malicious intent, especially toward Tsuneko who he felt such a connection to. And if he’s a good boy as others claim, then he obviously didn’t kill Tsuneko. As to whether or not he feels guilty about her death, I still think it’s unlikely he would have suspected himself as a murderer. It just doesn’t fit his persona.

Secondly, the main point of my post still stands: the anime is trying to paint Yozo sympathetically and this is unnecessary. A mystery might fit somewhat, but there are plenty of sequences in the novel to render instead. I would rather be faithful to adapting as much of what Dazai himself wrote rather than shoehorn in a mystery. I can’t help but feel the mystery (and horror elements of episode 2) was added simply to appeal to anime fans. I mean, yeah, we’ll see since it’s early, but like I also said, it’s not encouraging. I’m particularly interested in how the anime will portray Yoshiko.

Yes, he could feel anguish, but how does that change the fact that he was a sociopath? He clearly could not empathize with anyone else and that’s what a sociopath is.

Edit: On viewing the second episode, I was wrong about a particular point and have thus omitted it.

I actually liked the changes in the anime . . . except for the part of Yozo wanting to kill Tsuneko. I . . .prefer the novel version of him in that sense.

From that I remember, he wanted neither the book nor the lion mask at first, but later he mentions that he honestly prefers the book though he wrote lion mask in the notebook.

Yes, if he was forced to pick, he would have preferred the book, but I still think it’s more telling that when initially asked, he was unable to muster and answer and, in his own words, could only muster a dumb smile.

Pingback: L’Antre de la Fangirl » Impressions sur les séries de l’automne 2009

Sorry to bother but you are about the only one who has done a job at distinguish the two and i still haven’t read the novel.

1)Where can i find the novel in English?(It has got to be translated right?)

2)I read some more information at wikipedia which were few but read this:

Third Memorandum – Several years later, Ōba is expelled from University and falls into a relationship with a young and naïve woman. Ōba stops drinking and things seem to work out well until Horiki shows up, turning Ōba to self-destructivity again. Feeling distant from his wife, Ōba is once again driven to the verge of committing suicide, but unable to do so, he becomes an alcoholic and a morphine addict. He is eventually interned in a mental institution, and, upon release, moves to an isolated place, concluding the story with numb self-reflection.

It doesn’t refer to anything about his relationship with the glasses woman from the anime or about his wife being “raped in need of money” in the anime.Did these events occur in the novel or is it a Madhouse deviation from the plot?

3)Finally what happened at the ending of the anime is a little ambiguous.

He lost it and died from an overdose of drugs?

He just lost it and hallucinates?

I don’t have a clue…

1. You can buy the book on Amazon or any other reseller, I’m sure. It should be cheap.

2. It’s been a while and I don’t have the book with me. I don’t quite remember the glasses woman. As for his wife being raped, I don’t recall it being for money in the book. I think she was just raped.

3. I think it’s deliberately open for interpretation. He’s a loser and never could kill himself so I doubt he managed suicide. Probably just withdrew into his own world of self-hatred.