Aoi Bungaku ends with a pair of short stories from Akutagawa Ryunosuke. After watching these two episodes, I was left with a couple questions. First, did “The Spider’s Thread,” a children’s parable, really deserve one whole episode? Furthermore, why did a complex story like “Hell Screen” get so little time? I deliberate over Madhouse’s decisions in this entry.

“The Spider’s Thread”

The actual literature itself for “The Spider’s Thread” is quite short. It’s only about four pages in my edition of Penguin Classics translation. Nothing I could write here on the short story will probably be as in-depth as this commentary provided by a Timothy M. Kelly. When I first read “The Spider’s Thread,” I found it familiar, but I never made the connection to the parable found in The Brothers Karamazov. If you’re interested in Akutagawa and how he pieced together this story, I highly suggest that link.

As for the anime, on the other hand, I recommend it if only for the interesting depiction of Kandata’s hell:

But regarding the parable, I personally never quite followed the logic in the short story itself and the adaptation didn’t really help.

This robber had done many evil deeds: he had even killed people and burned down houses. But it seemed Kandata had performed one single act of goodness. Passing along a deep wood one day, he had noticed a tiny spider creeping along the wayside. His first thought was to stamp it to death, but as he raised his foot, he told himself, “No, no. Even this puny creature is a living thing. To take its life for no reason would be too cruel. And so he had let it pass unharmed. — page 38

Well, isn’t that odd?

First, Kandata’s own logic doesn’t make sense. He had been a wanton murderer up until this point, with the anime adaptation implying that he even killed a mother for no reason. So why, then, is it cruel to kill a spider but not a poor boy’s mom?

Second, was this truly a good deed? Well, considering I have never killed anyone in my life, I must have a whole lifetime of good deeds compared to Kandata. If you compare the Akutagawa’s short story to the parable in The Brothers Karamazov, a crucial difference stands out. In the parable, it is a woman instead of a man, but for all intents and purposes, they are both vile human beings. Here is the difference, however:

So her guardian angel stood and wondered what good deed of hers he could remember to tell God. “She once pulled up an onion in her garden,” said he, “and gave it to a beggar woman.” — Part Three, Book VII, Chapter 3: The Onion

I guess what I’m trying to say is that a moral obligation shouldn’t count as a good deed. A good deed should be what one calls supererogatory or, in other words, “going above and beyond the call of duty.” Okay, it’s debatable whether or not charity is a strict obligation, but I think our intuitions might agree that the woman in the parable did something greater than Kandata: he simply refused to take a life whereas the woman potentially saved a life.

In the end, I wonder if this really needed a full episode. To lengthen the story, a few additions were made and I’m not sure they contributed. We’re supposed to think Kandata is redeemable only if he was willing to help others escape from Hell.

But this child obscures his salvation. He’s a personal reminder that hammers home the fact that Kandata doesn’t deserve a second chance. The parable’s message should be about redemption, but the anime clearly doesn’t want us on Kandata’s side.

“Hell Screen”

The original story by Akutagawa actually spans across a lot of pages — 31 in my edition, to be exact. What we get in Madhouse’s adaptation is substantially abridged and I think it’s a shame. I think they completely altered the story.

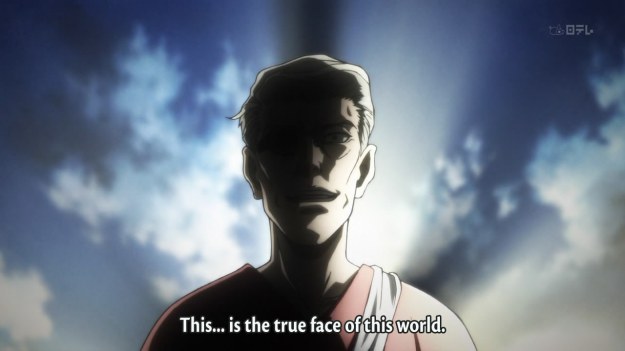

The anime’s portrayal of Yoshihide almost resembles a revolutionary.

He looks like he’s wearing an eye loupe, what you would typically find on a jeweler. In a sense, only he can see the fine details, the “jewel’s imperfections.” While everyone seems to herald the Lord (Lord Horikawa in the short story) of the kingdom, Yoshihide claims that he can see beyond the world for how it appears:

What we’re missing in the anime adaptation, however, is another depth to Yoshihide’s tortured artist character. As brilliant as he was, he was also bizarre and inhumanly cold; nothing could stand between him and the perfection of his craft. He would make outrageous demands, especially on his apprentices:

…Yoshihide said with a strange scowl, “I want to see a person in chains so do what I tell you. Sorry about this, but it will take just a little while.” Yoshihide could mouth apologetic phrases, but he issued his cold commands without the least show of sympathy. This particular apprentice was a well-built lad, who looked more suited to wielding a sword than a paintbrush, but even he must have been shocked by what happened. “I figured the Master had gone crazy and was going to kill me,” he told people again and again long afterward. Yoshihide was apparently annoyed by the young man’s slow preparations. Instead of waiting, he dragged out a narrow iron chain from heaven knows where and all but pounced on the apprentice’s back, wrenching the man’s arms behind him and winding him in the chain. Then he gave the end of the chain a cruel yank and sent the young man crashing down on the floor. — page 55

I think this should render the ending in a new light. Was his daughter’s sacrifice merely a cruel act by the Lord as punishment for painting that hell screen? Or did Yoshihide perhaps relish the chance to capture a moment no other artist could ever dream of seeing? This short story is autobiographical in nature because it’s more a meditation on what being an artist necessitates and requires. What are we willing to sacrifice to complete our masterpieces? Both in the short story and the anime, it is hinted that Yoshihide might have readily sacrificed humanity:

If it is even possible what? If it is even possible to burn somebody in that pillar of flame he requested? Akutagawa, the man behind stories such as “Rashomon” and “In a Bamboo Grove” (oddly enough, you’ll know the latter and not the former as Kurosawa’s Rashomon) liked to play with the truth. What was the truth behind Yoshihide’s thoughts? Unfortunately, the sadistic Lord completed the thought for Yoshihide and thus we will never know what Yoshihide was trying to say. The subtle difference between the short story and the adaptation, however, is that we don’t get to see Yoshihide’s reaction to the Lord’s promises in the anime:

“A thousand thanks to you, My Lord,” Yoshihide said with rare humility, his voice barely audible. — page 65

Again, Akutagawa liked to play with the truth, and in “Hell Screen,” it was hidden behind multiple layers of perspectives. The narrator of the short story is a servant sympathetic to the Lord and, as a result, usually has few positive things to say about Yoshihide. What was Yoshihide thinking at that moment? Did he sense the Lord’s cruel plans? Could he? How much can we trust the accounts of the servant?

The burning of his daughter also struck me as odd in the anime. It appeared so one-sided, almost redeeming of Yoshihide:

In contrast, compare the scene above in the anime to this passage from the short story:

But oh, how strange it was to see the painter now, standing absolutely rigid before the pillar of fire. Yoshihide — who only a few moments earlier had seemed to be suffering the torments of hell — stood there with arms locked across his chest as if he had forgotten even the presence of His Lordship, his whole wrinkled face now suffused with an inexpressible radiance — the radiance of religious ecstacy. — page 71

An important thing to note: in the short story, the Lord requested specifically a painting of Hell. In the anime, however, he requested something else entirely:

These changes are not accidental and completely alter the meaning of the story. The daughter in the anime becomes a martyr for the search of truth:

Madhouse even altered it to have Mitsuki burn at the stake rather than in the carriage as Akutagawa had originally written. The adaptation is thus not about an artist’s destructive ambitions. Rather, it becomes something else entirely: a story on how truth will conquer all, culminating in the comeuppance of the Lord himself:

But is this faithful to Akutagawa’s body of literature, works full of murky truths and morals in shades of gray?

I always wondered at the beginning what does “The masterpieces are blue” mean? and where to get sound track of the Aoi Bungaku series >.<

I’m not sure and a quick googling didn’t turn up anything meaningful. I did find that “aoi” is sometimes associated with youth, and young characters do feature prominently in these stories. Maybe someone else can tell us why the masterpieces are “aoi.”

aoi is a word in Japanese that didn’t distinguish in the beginning between blue and green. In that light and if we take the green instead of the blue, we get the phrase ‘the masterpieces are (ever)green’, that of course means they are immortal, classical.

Nice post. Now I’m interested more and more in getting down to comparisons and reading the originals. Although I’m of the opinion that each thing, original and adaption should be cherished seperately, for their own value. But indeed in the Spider’s Thread case this is questionable…

Oh, that’s pretty cool. I hadn’t thought about it like that. And I agree that adaptations can have their own spins. Sometimes, however, I just don’t understand the changes.

The moral of “The Spider’s Thread” seems kind of simple; if you’re a cold-hearted murderer, you’ll get what’s coming in hell. I liked the imagery of Kandata’s hell – disturbing yet artistic. But yeah, it did seem weird that the act of not killing the spider overpowered all the other cruel things he did and offered him a chance to possibly escape from hell (be redeemed?) But then he blew it by not trying to help others. That’s one helluva spider.

“Hell’s Screen” had another universal message about how those in power can be secretly corrupt. It had a lot to say in just one episode, about that, and also about how dangerously obsessive an artist can be with his work. I didn’t know it was so different from the originally story, especially with Yoshihide’s character.

Were these stories really children’s stories? They seem pretty dark.

That’s my issue with the adaptation: subtlety went out the window. The Lord wasn’t secretly corrupt at all in the anime. He was an outright cruel, heartless ruler, which is a significant change to his short story counterpart. It wasn’t just Yoshihide’s character that lost extra depth.

The Lord’s cruelty is much more discreet in the short stories. Let’s take the skeleton in the pillar, for example. The anime used it to show how evil the Lord is. It wasn’t quite so direct in the short story. The skeleton in the pillar was said (by the servant we can’t really trust) to ward off a vengeful God in the short story. We read it the first time and it’s like, “Oh.” But after finishing the story, you go back and wonder. Was it really to ward off the vengeful God, or was it something else? This extra depth is what defines Akutagawa’s style of storytelling, which I think is somewhat lacking in Madhouse’s adaptation.

The actual “The Spider’s Thread” was pretty short and simple. There weren’t any detailed scenes of Hell and it didn’t detail Kandata’s crimes either. It’s on par with Christian parables so it’s not too surprising to me that it’s for kids.

Since there’s no connection between the stories, which particular episodes would you recommend to someone who hasn’t read the originals for comparison?

I think they started with No Longer Human because it’s probably the easiest to relate to (despondent youth, etc. etc.). All of the stories are just fine though, regardless of whether or not you’ve read the originals. I just like to nitpick.

I wondered about the redemption aspect of the immolation scene. I haven’t read the original but the synopses I hastily googled don’t bring up this aspect of it. Which is not to say I dislike the idea. Nor do I hate the Lord dying. This series messed with every story they came across, which is their right. My only regret is that I wasn’t familiar with any of the stories they used. I couldn’t fully enjoy these new artists’ interpretations.

Taking liberties in the process of adapting anything is inevitable and almost expected, but it should be in a way, I think, that brings something unique to the story. I enjoyed the changes in “Run, Melos” and Kokoro. On the other hand, I felt Madhouse’s interpretation of “Hell Screen” made Yoshihide a bit too one-dimensional. Yoshihide was neither good nor bad in the short story; he was a complex character perhaps more devoted to his craft than his own daughter. The anime changed him quite a bit. Not only was he a great artist, he almost seemed like a good (morally speaking) artist, the only person in the kingdom who dared to stand against the Lord.

Привет всем!

Появился вопрос:

Возможно ли вставить видео-клипы на форум?

К примеру c youtube.com?

Если создал тему не там где нужно (пожалуйста:)) перенесите тему в соответствующий раздел.

Спасибо!

I find funny how Madhouse changed the two stories.”The Spider’s Thread” which is originally less dark became darker,and “Hell Screen” which is darker became lighter.

Also,the connected the two stories as we also observe at the ending where left stands the lord and right Kandata.

its very nice story

Perhaps spider was a test of humanity

No matter how evil or good his deeds were he was tested even if he didn’t save that spider back then

If he had alowed others to come with him to ”heaven” it would have shown that he is not rotten inside despite murders …

but he didn’t just because he was evil and his evil deeds were not from need but simply from his evilness

Hell Screen sounds like a really good story and it’s a shame they simplified it so much. As it is, I still enjoyed both episodes because of the nice visuals (Hell, especially, was beautifully animated, or so I thought), but the stories struck me as somewhat lacking.

I don’t even understand how saving others from Hell would have made Kandata be redeemed; saving awful human beings and bringing them to Heaven seems to me to be a bad deed, no matter how I look at it.

By the way, I recently started reading your blog and it convinced me to watch Aoi Bungaku so thanks. Although I found some stories more boring than others (Kokoro and Run, Melos), the two episodes of Cherry Blossoms were the best I’ve seen in a while.

If they are redeemed and truly repentant, then how is it a bad deed?

How do we know they’re redeemed and truly repentant? All we see is them climbing the spider’s thread, which was given specifically to Kandata for saving the spider. They’re just taking advantage of the fact it’s there.

Maybe they are repentant, but I saw nothing to indicate they were.

You have to consider that the story is just being rhetorical. Those people aren’t redeemed or saved. The entire purpose of the scene is simply to show that Kandata hasn’t changed. That was his personal test, he had one chance to prove himself, and he still failed. Whether those people are truly redeemed or not — whether they’re even real or not — isn’t really important. And I’m sure someone else up there will make the final judgment on those souls anyway had Kandata not been the selfish person that he is.